In the context of religious philosophy, universalism states that all the different religions are simply different paths to one common goal. Universalism also states that all religions refer to the same spiritual reality but using different language. They emphasise that there is one God, regardless of name, and spirituality is the experience of the divine. Perennial philosophy has similar ideas where their main belief is that there is a single truth that is explained in different ways. This single truth can be God, Brahman etc. While the differences were attributed to cultural development, concepts like religious rituals, prayer, sacred places, at a high-level are common to all religions. Thus universalism, perennialism etc. create the illusion of homogeneity of goal by linking these diverse activities to a single ultimate end. This is a recipe for religious peace, with the focus on humanity rather than the notion of a supernatural entity called God which is common.

Even scholars have found ideas such as universalism always hard to explain in practice. While stories related to creation of the universe, the actions of different gods can all be viewed as part of different paths, the challenging part is the definition of the common goal or single truth. How does one reconcile Samsara (the cycle of birth and death) leading to Moksha and the notion of eternal heaven or hell? Also how does reconcile theistic religions with non-theistic religions like Buddhism and Jainism. How are Nirvana and salvation identical? How does the notion of Dharma (which is contextual) relate to fixed commandments? Are all these differences parts of the different paths? If so, what is the goal?

While the formal notion of universalism arose in Christianity, there were many theologians who were opposed to this. They felt that those who were removing Christ from the central role in salvation, were not truly Christian. Liberal theologians argued that Christ represents the abstract ultimate entity. Similarly, the idea of universalism raised in the context of Islam (e.g., by the Sufis) were also decried by the orthodox people, who insisted that Allah can be the only name used. Many of these hardliners reiterated the derogatory idea of false gods, or classifying religions as pagan. Some of the colonial powers used the idea of universalism or perennial philosophy to undermine the religions that were followed in the colonies. They argued that since all religions are the same, there is nothing unique in the religion of the colonies. They also argued that the actual practice of the religion were inferior at best and demonic at worst. Hence a particular path was superior to others.

There are many followers of Hinduism who assert that Hinduism views all religions as equal. Some of them go as far as claiming that it is the only religion that has this view. Therefore, they conclude that Hinduism is superior to other religions. Clearly, this goes against the equality view. Statements like, “Different religions are nothing but different paths to the same goal“, are not very helpful. Even within different schools of thought in Hinduism, this may not hold. For example, the notion of Moksha as the goal may be accepted by the majority (e.g., Gaudidya Vaishanvism does not accept it), but what is Moksha can differ. Just because a common word is used, does not mean that the actual goal is the same.

In this note, I will show how one can be accepting of other religions without asserting universalism. This can be the basis of comparative studies that acknowledges the differences, along with the common factors, between the different religions. I will restrict myself to general principles and apply them to different Darshanas in Hinduism. My aim is to show that many of the ideas are quite distinct and hence cannot be said to be superior or inferior to other ideas. This will also show that each Darshana has unique elements and thus needed to be treated as being different from other Darshanas.

Before British colonialism, Hinduism, at least in general, did not claim that all religions are the same. Religious freedom and tolerance was part of its pluralistic ideas. That is, it always accepted that people should have the freedom to follow other religions. But this was not based on the idea that all religions are the same. Thus pluralism was not based on some abstract notion of equality. There was no mention of a single ultimate goal. During the colonial period, some Hindus, who were influenced by universalism, started to translate pluralism as sameness of goal. The argument of universalism was also accepted as it could be used to repel the attacks of idolatry etc. which played right into the hands of the Christian missionaries who stressed that Hinduism had nothing to offer. Therefore, there was no reason for Hinduism to exist as a separate religion.

The goal of universalism, namely to integrate the different religious traditions, is clearly noble. The plurality is capped with a single truth. But this well intentioned idea, does prevent robust intellectual discussions as the differences between the different philosophies does not really matter. For example, the different theories related to causation will be dismissed as irrelevant. Also trying to capture a single truth of different concepts such as Purusha (in Samkhya), formless Brahman (in Advaita), Brahman with form (in Vishistadvaita), theistic models like Vaishanvism (where Vishnu is the ultimate), Shaivism (where Shiva is the ultimate), Shaktaism (where Parvati is the ultimate) will invariable lead to unnecessary dispute. For example, a strong believer in a specific theistic tradition is not going to agree that Shiva, Vishnu and Parvati are all the same. So it is best that these entities are not comparable. That is, Shiva cannot be compared to Vishnu, Parvati, Brahman etc. in general. But one needs to be able to equate Shiva and Brahman when describing non-dual Shaivism (e.g., Kashmir Shaivism as explained by Abhinavgutpa). That is why, Hindu scholars have opposed universalism as it reduces the importance of the benefits of the diversity of ideas that are part of Hinduism and allows each belief system to have its own ultimate, without equating them.

As noted in my previous article, Hinduism supports polytheism, monotheism, kathenotheism and henotheism. These ideas are all incomparable. There is no natural ordering of these ideas. Each path (or strand) within Hinduism has its own concepts and an ordering of these concepts but different paths can have different concepts and orderings. I now present a few examples. In Advaita, Brahman is the ultimate with Shiva and Vishnu below Brahman as they are dependent on Brahman. Shiva and Vishnu are not comparable. In Samkhya, there is no notion of Brahman although the concept of Purusha can be related to Brahman. The universe is dependent on Prakriti who is dual to the Purusha. Technically, Purusha is the ultimate, but Prakriti does not depend on Purusha for its existence. Vaishnavism and Shaivism do not deny Shiva’s or Vishnu’s existence respectively. Thus they share the idea of Shiva and Vishnu. But Vaishnavism makes Shiva subservient to Vishnu while Shaivism does the opposite.

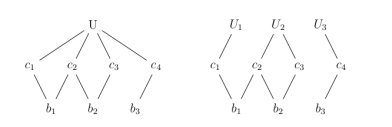

In general, we have a collection of concepts (say C). A specific religion will use the relevant subset of C (say S). The concepts in S are then partially ordered (i.e., may support items which are not comparable). Two different religions may share common concepts but they could be ordered differently. Hence saying all religions are the same or pretty much the same is not very useful. This does not recognise the the distinct theories that underpin the different traditions. As noted by many scholars, the different religions are not like different brands of the same medicine providing the same cure. Instead of saying that the different religions all lead to the same goal, it is better to recognise each person’s spiritual path as a different religion without any reference to a specific common goal. This does not mean statements such as God treats people of all religions the same are wrong. It just represents one of the paths. I conclude with a mathematical interpretation of the statement Ekam Sat Vipra Bahudha Vadanti (which states that there is one “truth”). Each school of thought or path has a unique ultimate; therefore there is one “truth”. But there is no reason to assert that the different ultimates are the same. Thus these paths/schools of thought can be organised as a partial order which need not be a lattice. This is shown below where the diagram on the left has a single ultimate while the diagram on the right has multiple “ultimates”. For example, starting from the base concept of b1 or b2, one can reach ultimate U1 or U2 (depending on interpretation), while from b3 one will reach only U3.

References:

- W. E. Paden: Comparative religion, 2005

- F. G. Morales: Does Hinduism Teach That All Religions Are The Same?, 2008

- J. D. Long: Universalism in Hinduism, 2011

- D. McKanan: Unitarianism, Universalism, and Unitarian Universalism, 2013

- J. D. Long: Hindu Relations with the Religious Other, 2014

Very insightful, Paddy. It’s just the way things are. One person saying ‘Mine is the same as yours’ is invariably nudged aside by a thousand preaching ‘Mine is bigger than yours’.

LikeLike

Thanks Chamkaur. It is better to live and let live.

LikeLike